Last month, I wrote about Marc Jacobs’ work with Stephen Sprouse as an introduction into his collaborations with some of the world’s leading contemporary artists. This month, we’ll continue that exploration with a look at his work with renowned performance artist, Vanessa Beecroft.

Jacobs’ collaborations with fashion designers and artists like Stephen Sprouse and Takashi Murakami are the partnerships which have garnered the most public acclaim, but it is his more avant-garde explorations of the brand which have defined Jacobs as a true artistic innovator — such as his work with Vanessa Beecroft, whose autobiographical performance art generally involves public configurations of nude women in various states of accessorized undress.

A notoriously aggressive personality, Beecroft is an exercise bulimic who is extremely public about how her nearly lifelong eating disorder — also the the crux of her work. Although performance art is not the only genre in which she creates — she also paints and draws, and has made a decades-long art project from her eating diary, a daily log of every calorie she intakes — she is best known for her provocatively staged public events. The majority of her performance pieces are documented through photography, which she cites as a necessary, but misrepresented portrayal of what her pieces are meant to accomplish. Her obsessive interest in fashion colors her stagings, for her models are always styled in designer heels (often donated by fashion designers like Prada and Tom Ford who interested in Beecroft’s work and want to associate with her artistically), wigs, makeup, and various sorts of accessories. So often, the resulting photograph is usually more akin to a high fashion editorial than what a Beecroft piece actually is: a slow, hours-long experience where the models are required to simply stand nude in front of a clothed audience, their increasingly palpable shame and discomfort symbolically (although not overtly) mirroring Beecroft’s experience as a disordered individual hideously fiendishly obsessed with her weight and appearance.

There’s a certain taboo quality about the psychological origins of Beecroft’s work that makes it potentially unsettling as a collaboration with a luxury brand as iconic as Louis Vuitton. The fashion industry is consistently under fire by critics who claim that industry standards regarding sample sizes and the preferred body shapes for models promote an unhealthy female body image. Therefore, it could potentially be construed that Jacobs’ collaborations with Beecroft are an indirect, or direct, support of eating disorders or an unhealthy lifestyle.

Regardless, I am fascinated by Beecroft’s work, and the genuine way in which her series has developed conceptually from her eschewing performance art, to inadvertently discovering during a college art exhibition that the inclusion of actual women into her work was a powerful enhancement. I’m especially impressed with Louis Vuitton’s incorporation of her performances into openings at some of their stores, in addition to staging some of her pieces at Espace Louis Vuitton Champs-Elysee, an art-specific space in Paris (there is an Espace in Tokyo, as well) built and curated by Louis Vuitton. There is an honesty to Beecroft’s work that doesn’t attempt to inflate meaning, or even capitalize on the elements which could be, to many, considered shocking. This genuine embracing of concept works well within the Louis Vuitton sphere, paralleling Jacobs’ design work at Louis Vuitton. Beautiful women, adorned with various symbols of glamour, surrounded by inimitable luxury, but yet also exuding palpable discomfort and shame — realities which no woman is immune to, no matter how perfect their bodies, or surroundings. “I became a performance artist by mistake,” Beecroft said in an interview with Judith Thurman for the The New Yorker. “There is something vulgar about the genre: its human reality. … I like to know that each of [the girls] has a weakness. Seeing other women’s bodies is a relief, because even the most desirable body bears the scars of an imperfect life.”

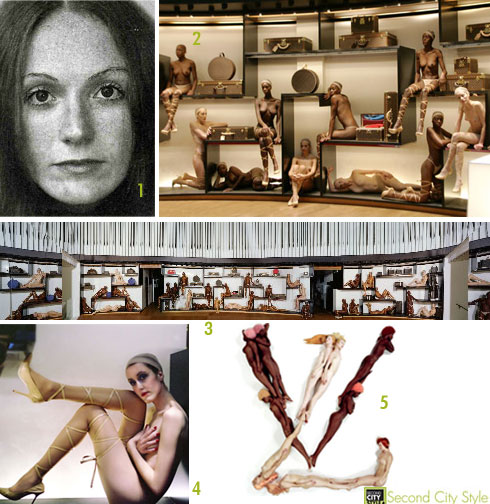

These imperfect lives were prominently on display at the reopening of the Louis Vuitton flagship on the Champs-Elysee in October 2005, which featured 30 black and white models (chosen by Beecroft) who were arranged amongst the shelves in the center of the atrium, their contorted bodies draped along Louis Vuitton trunks. The nude models were wearing bright coral lipstick and shimmery purple eyeshadow, an exuberant approach to makeup that shined in stark contrast to the wig caps imprisoning their hair. Their legs were wrapped in leather laces that stemmed from their high heels and encircled their calves like those from a ballerina’s point shoes. Unlike the glamour Beecroft identified in many of the photo documents of her stagings, the women at the Louis Vuitton Champs-Elysee opening seem sullen, detached and tired, with their posture shrunken as if to hide themselves as much as possible, despite their blatant nudity.

Although certainly there is an dynamic aesthetic at work here, Jacobs’ incorporation of Beecroft’s performance art goes far beyond the impact of a neon-graffitied Keepall bag, or the impressiveness of an expertly designed boutique. I am so taken with this collaboration because he incorporates fashion with humanity — and not just the humanity of the models, or the humanity of the customer as seen through the models, but the humanity of the artist, as well. Because Beecroft could be Jacobs’ consumer — wealthy, elite, cultured, strumming about the highest tiers of society, but, ultimately, deeply damaged (as is Jacobs — his battle with drugs and alcohol and bouts with rehab are a leitmotif of his life and career that rarely escape an interview).

For the same opening of Louis Vuitton Champs-Elysee, Beecroft staged an alternate piece, which featured a group of black and white women positioned in the middle of a massive room at the Petit Palais. An image of the women’s bodies was projected behind them, and viewers were able to see that their bodies spelled out “LV” — white for the L and black for the V. Beecroft was inspired to create this performance after finding an old magazine at a flea market in New York, which featured images of Erte’s human alphabet that he illustrated in the late 1920s. Of Erte’s project, Roland Barthes said, “it is […] an illusion to think that fashion is obsessed with the body. Fashion is obsessed with that other thing that Erte discovered, with the extreme lucidity of the artist, and that is the Letter, the inscription of the body in a systematic space of signs.” This observation is significantly apt when applied to Beecroft’s work with Jacobs.

Not only is the Louis Vuitton brand home to one of the most ubiquitous visual logos in the industry, but the brand itself is much more than just a purveyor of clothing or a tool for improving the body. Louis Vuitton emphasizes a lifestyle; a lifestyle that has gained attraction via the popularity of certain signs, but also a lifestyle that puts emphasis on culture and an all-encompassing intellectual wellness, rather than just a shallow obsession with objects. By so richly highlighting these signs with the presence of raw humanity, Jacobs and Beecroft elevate the impact of both their work, tying it in to something bigger than themselves and more powerful than just an object.

Photos: 1. Vanessa Beecroft, artobserved.com, 2. – 4. Louis Vuitton Champs-Elysee Exhibit, vanessabeecroft.com, 5. Black White LV, styleite.com

—Amanda Aldinger

Image Layout: Molly Murphy